Egypt and Tunisia appear to be a laboratory of democracy as well as an example of the cul-de-sac in which the political Islam finds itself. In both countries the Islamist parties have won – more or less democratically – the elections but are still unable to govern properly. Even worse, they are losing in popularity. This impasse has two major causes: the complex agenda which numerous foreign forces are trying to implement in the region and the internal ideological dysfunctioning which a confrontation with the true practice of power brings along, since it is a mistake to think that a society could be forced to gather under one unique flag in the name of religion. In such a context, what kind of democracy could be established? The transition seems to last very long, and the road to true stability is extremely painful; its cost is inestimable, if not totally unaffordable.

Egypt and Tunisia appear to be a laboratory of democracy as well as an example of the cul-de-sac in which the political Islam finds itself. In both countries the Islamist parties have won – more or less democratically – the elections but are still unable to govern properly. Even worse, they are losing in popularity. This impasse has two major causes: the complex agenda which numerous foreign forces are trying to implement in the region and the internal ideological dysfunctioning which a confrontation with the true practice of power brings along, since it is a mistake to think that a society could be forced to gather under one unique flag in the name of religion. In such a context, what kind of democracy could be established? The transition seems to last very long, and the road to true stability is extremely painful; its cost is inestimable, if not totally unaffordable.

” According to recent polls, the coalition has no majority anymore. Ennahda is still the biggest party despite the regression of its popularity, but its two allies are the big losers. The two other big parties should be the Union for Tunisia and the Front Populaire. If new elections would be held, the Islamist party and the former party of the dictatorship would be neck and neck. In such a situation no coalition seems to be possible. This means, as a newspaper recently wrote, that the Islamists lost the legitimacy and are losing the power ”

The political scene in Tunisia:a moving puzzle

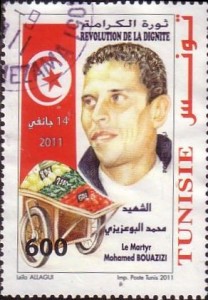

In Tunisia, the transitional period seems to take more time than expected. Right after the fall of the former regime a process of multilayered reconstruction started. It was supposed to last one single year and to end with the election of a new stable and democratic government. The deadline has been largely surpassed. The elaboration of the new constitution and the organisation of new elections are expected, unless any postponement comes up, in approximately one year. This delay is apparently justified by the insecurity that lies beneath a deterioration of the economy and seems to make any political process impossible. This is perhaps not untrue. But the main fact behind this inertia is a deep political crisis related to the new balance of powers.

Whatever the reason, this country is in reality run by an illegitimate government. It can be, in a democratic country, that after elections it takes some time to establish a government of coalition. This is in fact what happens in Belgium or the Netherlands. During this period of negotiating and bargaining, the country is only run by its institutions and the administration continues to take care of the functioning of all structures: finances, diplomacy, healthcare, education… What occurs in Tunisia, where institutions are being re-invented, is an institutional vacuum. When the State doesn’t exist, nothing works. The deadline of legitimacy ought to become the turning point which would lead towards a stable situation. If not, it will push the country into a spiral of non-governance.

Tunisia is going awry for months already, and still no deadline for new elections is appointed. The political crisis reached the unbearable point at which the political parties are not able to agree on any political concept. Due to the impossibility to get hold of reality, the coalition that resulted from the prior elections cracked and threw the sponge. After a few months of negotiations about a new cabinet reshuffle in order to reclaim the public opinion, the huge differences between the various parties, their fight to get as many positions as possible and the will of the Islamist party to keep full power over the state prevented them from any possibility to reach a common ground. At the same time, every one of these parties had to face its own inner wars.

As a result of all this, the political scene started to move and produce new phenomenons. Parties’ representatives in the parliament move from one block to another. Those who resigned from their political party joined another one or created a new one. At the same time, the opposition, while looking for a new strategy, developed the concept of “electoral coalition”. These are groups of political parties joining together in a kind of front and prepared to collaborate for the upcoming elections. Two big fronts emerged from this process and obviously changed the balance of powers: “The Union for Tunisia”, a centrist front built around Nida Tounes, a heritage of the former party of the dictatorship, and the “Front Populaire”, a leftist front which core is the Tunisian Communist Party that recently was re-baptized Labour Party.

This is a very dangerous turn in the political evolution of the transition. Those who have the power recognize that their chances to stay in the government are diminishing, and develop even more fear to face new elections. Many media mention how Ennahda, the Islamist party, lost the People (Martine Gozlan on Marianne-Tunisie). According to recent polls, the coalition has no majority anymore. Ennahda is still the biggest party despite the regression of its popularity, but its two allies are the big losers. The two other big parties should be the Union for Tunisia and the Front Populaire. If new elections would be held, the Islamist party and the former party of the dictatorship would be neck and neck. In such a situation no coalition seems to be possible. This means, as a newspaper recently wrote, that the Islamists lost the legitimacy and are losing the power ((1)) .

The coalition tries to maintain its legitimacy artificially despite its illegality and in spite of all its internal troubles. In addition to that, and fearing a complete loss of its grip on the population, it goes to the streets where the opposition is getting more and more present. After the terrible elimination of Chokri Belaid, one the leaders of the leftist front, a spontaneous demonstration against the violence and against Ennahda took place in the capital Tunis. The concerned party organised a counter demonstration a few days later in order to respond to the accusations and to defend its legitimacy. The difference between the two demonstrations is very meaningful: 1.400.000 contra and almost 16.000 pro. (NB: the Tunisian population counts around 10 million)((2)) .

On the other hand, the institutional vacuum, mainly in terms of security, is a serious threat to any peaceful political debate. When it leads up to the physical elimination of leaders of the opposition, it means that there is no place for differences. The murder of Chokri Belaid is the sign of a very dangerous escalation in the political game. For a long time there were death threats against intellectuals, artists and political leaders. A local representative of Nida Tounes in the south of the country was lynched during a demonstration against the government. A few months later, for the first time after the revolution, a political leader was killed in a planned and methodical way. Everybody accused the Islamists, if not of being guilty of the attack, at least of being politically and morally responsible. Even after the author of the crime was found, nobody else was accused. It was a political crime and it is not enough to arrest the executor. Those responsible must be unmasked.

Is Political Islam ahistorical?

Insecurity is indeed the result of a certain way of dealing with politics. It is not by chance that we see the same kind of violence in Egypt and in Tunisia at a time when the two countries are run by the same ideology: the Muslim Brotherhood. For the first time in Modern Age this version of Political Islam, besides the Iranian regime of The Ayatollah and the regime of the Taliban in Afghanistan, is confronted to the praxis of power and hence to its contradictions with modernity.

The first contradiction has to do with religion itself. A religious party in a Muslim country is supposed to have the absolute majority because opposition to the party means blasphemy. That’s why the Islamist parties can count on large amounts of naive believers. The problem is that once they get the power, they are confronted to concrete reality. Very quickly voters will see the differences between religious and political promises. Promises of God can be verified only in another life, but promises made by politicians need to become manifest within months or even weeks after the elections.

Most of the voters on Islamist parties support them not because they are convinced by their political program, which they don’t really have, but only because they believe in the same God or even worse: because they are afraid to be associated with blasphemy. When you start to say that you are the party of God, you are pointing at the others as parties of the Devil. From such a point of view, namely the exclusion of any otherness, how could a democracy be possible? Very often the argument of belief appears in Political Islamist’ speeches and secular opposition is being accused of atheism. Chokri Belaid was one of these opposition leaders who was frequently accused of blasphemy, even when he never said anything against religion but only against the use of religion for political purposes. Because of this he was, like many other intellectuals, accused of being an enemy of the Islam and God.

In the conservative and radical interpretation of Chariaa, this is simply synonym of fatwa of death. The Sheikh says a word and the young brainwashed Muslim translates it into a terrible act. Right after the murder of the leftist leader the crowd in the streets shouted the name of the Islamist leader Ghannouchi, pointing at him as the first responsible, if not for some extremists as the sponsor of the crime. Anyhow, violence reached such a high point of mix-up that nobody knows to whom the crime actually profits.

When the State is not able to secure the country or when the government intentionally lets violence spread, it is responsible of the consequences. There exists a very Machiavellic strategy in times of crises of power, which is based on keeping the people busy with violence and fear in order to not let them focus on the political manoeuvres of the dictator. This seems to work when a regime is declining and a new one is overtaking a chaotic situation. This is the spiral of violence which accompanies all revolutions. It is composed of two momentums: the first is the repression of the uprising by tyranny; the second is the terror necessary for the settlement of a new regime and new institutions.

During the French Revolution, the Human Rights Declaration took place under the “Reign of Terror”. Ghannouchi considers himself to be less like Robespierre and more like the Iranian Ayatollah Khomeini. This has not only to do with the common ideological background of the Iranian but also with the way Islamism in Tunisia is trying to imitate the way the ayatollahs seized power in Iran after 1979. Like Khomeini, Ghannouchi came back from exile after Ben Ali was forced to step down. The way he was welcomed by his partisans is comparable to the way the Ayatollah came back to his homeland after the fall of the Shah. Tunisian radicals also tried to attack the American Embassy, like the Iranians did. The only difference, but also a great difference, is that Ghannouchi is in power because he is officially tolerated by the Americans. This was not the case with Khomeini.

Many signs indicate that there is a temptation to turn the events in Tunisia into a copy of the Iranian revolution. The people’s uprising is being deviated to a religious dimension which was never an important argument in the claims of the demonstrators. The scenario seems to be the same as it was in Iran: having got the power, it is time to eliminate the opposition. From time to time, declarations by the Islamist leaders give indications about their underlying plans. Once, the Prime Minister spoke of Al-Khalifa (the successor of the Prophet) which is the archaic regime of governance built on the fact that one leader is replacing the prophet as head of the nation and governing in the name of God. Many times the Sheikh declared that his party got the power as God’s will and therefore never shall leave it.

These messages have two groups of recipients, to whom they mean something different. On the one hand they are intended to insure the party members that they are on the right way. On the other hand they are meant as a threat towards the opposition.

The murder of Chokri Belaid and the death threat against many politicians, such as members of the labour union, can be seen as an embodiment of the process which aim it is to definitely eliminate any political opposition. This cannot be without physical control of the field. When you are in control of the State you get full power over its institutions and mainly those concerning security and administration. When you cannot abuse them by manipulation, it is easier to infiltrate them. There are indeed lots of talks about a parallel police inside the Ministry of Interior. Some media (www.tunisiefocus.com) see the resigning of some high officers as a confirmation of this phenomenon.

In addition to this, the Islamists in Tunisia supported the “Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution”. These corpses emerged during the uprising and remained active afterwards in order to defend the claims of the revolution, just like the Iranian Guards of the Revolution. As a matter of fact, members of these Leagues were involved in the lynching of Lotfi Nagdh, a local militant of an opposition party. The dissolution of these leagues is the main claim of the opposition and the liberal civil society, just as the Lowers Order, the Tunisian Organisation of Human Rights and the principal Labour Union. They all consider these corpses as the militia of the Islamist political parties and therefore responsible of the insecure atmosphere in the country.

There is a kind of arm wrestling going on between two tendencies. The first one wants the institutions of security to stay politically neutral and work in an appropriate way. This is the basis of any democratic game. The other one wants it to work according to a political agenda. The latter considers that it has the responsibility to carry on the revolution and that this is no longer the matter of anybody else. Before the uprising, the Islamists were not active in civil society. The rise of the Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution right after Ben Ali stepped down, was the only possibility for them to become present in the field. They failed to integrate any constituted organisations, like those of lowers, labour unions, student’s organisations, etc. After the first elections and the arrival of an Islamist leader at the head of the Ministry of Interior, all these hybrid bodies and other even more ambiguous militias started to substitute the regular forces of security.

This is emerging from what the supreme chief of Islamism in Tunisia called “Social Scramble”, in the sense of the period which a society in chaos needs to settle and in which the clash between differences will progressively calm down. However, this theory is above all meant as a rhetoric discourse to justify the existence and the actions of anarchic groups such as salafists and jihadists. These make the rain or shine in the country: ransacking of mausoleums and cinemas, intimidation of artists and intellectuals accusing them of blasphemy, prevention of opposition meetings, etc. The escalation of the so-called Social Scramble led to the first liquidation of political representatives and is the background behind the dysfunction of the machinery of the state. This is perhaps why Jeune Afrique, the pan-African magazine, called Ghannouchi “the man who betrayed the revolution ” ((3)), because he and his party confiscated the claim of the people and turned it to a completely different direction.

” Let us not forget that the repression of Political Islam in both Algeria and Tunisia started more than twenty years ago in reaction to its threat. The two countries are tightly connected to each other. Now that the latter is run by Ennahda, which is an ally of the enemies of the Algerian regime (Algerian Islamists and their sponsors), it seems that the noose around Algeria tightens more and more. Does this mean Tunisia is nothing else than the small fish used to catch the big one? ”

The monopoly game of hegemonic powers

There is an incompatibility between the hope of the people and the political agenda which Tunisian Islamism wants to establish in the country. The mosaic of Islamism is formed by tendencies which are inspired by foreign models: the Egyptian Brotherhood, Iranian Shiism, the Afghan Taliban, Saudian Wahhabism and even the more widespread and scattered jihadism of Al-Qaida. All this turns Tunisia into a theater for a fight over its denaturation. If the seemingly moderated party has the power, this doesn’t mean that it doesn’t coordinate with the others which are more radical. It’s even not obvious that there are any real differences from the point of view of ideology and political strategy. The biggest party is the one which speaks for all these different variations and appears like an umbrella to all tendencies of Islamism in Tunisia.

Ennahda mainly aims to reproduce the Saudian model in its leadership of the Muslim world. Not only is Saudi Arabia the principal sponsor of the Muslim movement, it also has a direct influence on the direction in which the party has to lead the country and on the way it works and organizes itself. The only party to have a Shura Council is Ennahda, which is copied from the Saudian advisory council of the king. Members of the latter are not elected but appointed by the king and mostly recruited among members of the royal family or the chiefs of the tribes. Just as the prime minister wanted to do once, at a time when it was impossible to compose a new government.

He gathered a few respectable persons and called this group “the Council of Wise Tunisians”, a kind of Council of Lords which was supposed to advice his highness on how things should be. Instead of turning to the parliament, where representatives of the people are elected for this kind of duties, he appointed himself Prince/Khalifa and created purely by personal decision, even though temporarily, a new state organ. He wanted to copy his own party’s organization, which copies the Saudian model; an avatar of the archaic Islamic regime from the time of the prophet Mohamed, which is a feudal structure of governance from 14 centuries ago that contradicts the basic principals of modern democracy such as the suffrage and the involvement of the people in the process of its governance.

Ennahda itself is deeply schizophrenic and leads Tunisia into the same schizophrenia. On the one hand it tries to be cohesive with modernity by being democratic or at least by appearing as such. On the other hand it owes allegiance to its strategic sponsors. This has to do with all kinds of ideological ramifications but also with all the different foreign partners and agendas with which it has to cope. To the westerners it has to show that it respects multipartism, freedom of press and human rights; to the Gulf oligarchies it has to insure that the country will culturally go back to a feudal system where women have no longer the right to drive a car, for example.

This explains the contradiction on the level of diplomatic relations. The former dictator is protected by king Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud since he stepped down, although he is tried for life imprisonment in his own country. The same can be said about his son in law, who is under the protection of another prince of the Gulf, Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, oligarch of Qatar. They are protected against international law and against the will of Tunisians who want them back in the country. This seems to be one of the compromises between the transitional Tunisian government and its allies.

Outwardly the two oligarchies support the Tunisian revolution, but in reality they don’t want it to develop in the direction of a real democracy. They are no democracies themselves, so it is not in their interest that new examples of modern Muslim countries would emerge. They need to keep controlling all changes, which is why they intervene every time a regime falls. They did it indirectly in Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen. They were less discreet in Libya and even more obviously engaged in Syria. Whether they are forced to play the role of the ally of the USA in the region as a way to pay back the dept of the destruction of Iraq, as part of the complot against Iran or as part of the great US plan to reconfigure the whole region in order to control its resources, is not clear. Probably for these reasons all together, in addition to their own hegemonic agenda.

This agenda is ideological but also neo-capitalist. When we look at the so-called Arab world, we see that the only country where Saudi Arabia and Qatar still don’t have any influence is Algeria. This country is the biggest, the richest and the most sovereign country in the region. Literally it is the only truly independent country. Its fall is probably planned after the destruction of Iraq, Libya and now Syria. All of these countries were run by strong regimes out of reach of any foreign influence. There was a try to destabilize Algeria after the elections of 1988 which led to a civil war that lasted some ten years. But no foreign agenda could get any grip on the situation.

Now Algeria is surrounded by Islamist governments: Libya, Tunisia and Morocco. There was an attempt to control Mali in the south of the country. It seems that Qatar logistically supported (4) the rebels to invade it. France, another ally of the oligarchies, has too many interests in Mali to allow it to fall in an allegiance to any other part. There we could see the Theater of conflict of interests. First the Jihadists conquered more than half of the country thanks to the help of Qatar. But when the French interceded they had to retreat quickly. It also seems that Qatar helped to evacuate some of its mercenaries via special illegal charters (5) . That the French could not have known about this and could not prevent it, is dubious. But the two parts have another more important goal.

In a recent official speech Bouteflika, the Algerian President, had to speak up about a complot against his country and linked it to what is happening in the neighborhood (6) . Reality seems to confirm this apprehension: many armed groups are active on the border with Tunisia and many Tunisians were involved in the attack of Inaminas, a gaz station in the Algerian desert. Furthermore, this happened only a few days after the murder of Chokri Belaid, the Tunisian leftist leader, just when some started to accuse the Algerian secret service of it or pointed at an Algerian network of Islamists to be behind the murder. For others this is only a way to distract the people from the real internal danger of violence. No matter what the truth is, it is clear enough that Algeria is in the line of fire of certain head-hunters.

It looks like the region is progressively moving towards a division in two blocs: on one side Syria, Hezbollah, Iran; on the other side the front led by the two wahhabist countries Qatar and Saudi Arabia. The latter two are trying to recruit the weak countries because of their social and political instability by orientating them or even fully controlling them. As long as Algeria is out of their reach, it remains a weakening element for the great alliance they intend to build. They are like starving scavengers looking for weak animals to devour. Their own weakness means that they are losing the fight against the other fattened beasts.

Let us not forget that the repression of Political Islam in both Algeria and Tunisia started more than twenty years ago in reaction to its threat. The two countries are tightly connected to each other. Now that the latter is run by Ennahda, which is an ally of the enemies of the Algerian regime (Algerian Islamists and their sponsors), it seems that the noose around Algeria tightens more and more. Does this mean Tunisia is nothing else than the small fish used to catch the big one? This could be one of the reasons why even the Islamist agenda is not considered for itself, like it was in Iran. Khomeini had no foreign agenda, which is why he could build the Islamic Republic despite the war with Iraq, a war financed by the gulf oligarchies. So when you are dependent of all kinds of agenda’s except one of your own, you will never be able to build a country that you can fully govern; you will only get land of which you are a leaseholder, never a real owner. Instead of being a modern sovereign prince proudly chosen by his own people, you prefer to serve as a vassal in an anachronistic feudal servitude to the interests of other overlords.

1) Nizar Bahloul in www.tunisie-news.com.

2) According to the Tunisian web-magazine Kapitalis.

4) According to Mehdi Lazar in L’Express, December 2012.

5) oumma.com

6) albawaba.com