The Slovenian philosopher tells Benjamin Ramm that the survival of the European project is too important to be left to a referendum.

The Slovenian philosopher tells Benjamin Ramm that the survival of the European project is too important to be left to a referendum.

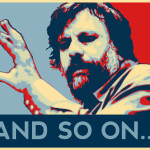

Slavoj Žižek is animated about Brexit. “You know, popular opinion is not always right”, he insists. “Sometimes I think one has to violate the will of the majority”. This sentiment may surprise some of his admirers, but our discussion highlights his long-standing ambivalence about democracy. The despair and confusion of the past week has only reinforced his outlook. Reflecting on the Leave voters who were alarmed to learn that their side had actually won, Žižek quips: “The worst surprise is to get what you want!”

I ask whether the referendum posed a false choice, offering a nation state solution to transnational problems. “Precisely. The EU is in a state of inertia, and I share this rage of the people. But what will be the result? Britain will lose months, years in protracted negotiations with a shitty compromise at the end – during which time the space for real change will have diminished. The British attitude, of leaving the EU to its fate, is the logic of the wrong era in an age of global problems: ecology, biotechnology, intellectual property. Britain all alone will be even more vulnerable, exposed to the pressure of international capital without any of the protections. I don’t see any strength gained in standing alone”.

The final weeks of the referendum campaign were characterized by strong criticism of direct democracy, elements of which have been revived by progressives in recent years (citizens juries, participatory budgeting, etc). What of the Marxist tradition of celebrating this model, as espoused by CLR James? “Direct democracy is the last Leftist myth”, Žižek tells me. “When there is a genuine democratic moment – when you really have to decide – it’s because there is a crisis”. He says referendums are impractical for resolving transnational challenges, and would prefer “the appearance of a free decision, discretely guided” by a discerning elite.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised by these remarks: Žižek has frequently defended the Leninist idea of a ‘vanguard’, and has witnessed firsthand the dangers of populism in eastern Europe. (Walter Benjamin, surveying the surge of nationalism in the early 1930s, came to a similar conclusion). Žižek’s prescription is an intriguing riff on Marx: “good alienation”, in which “power is anonymous and functioning in an efficient way”. He imagines an “invisible state, whose mechanisms work in the background” – a sort of “bureaucratic socialism, but not in the Stalinist sense”. (The problem, he tells me, was that “Stalin’s bureaucracy didn’t function, lurching from one emergency state to another” – a debatable assertion).

This appetite for technocracy ought to make Žižek an enthusiastic supporter of the EU, an institution that reflects Saint-Simon’s aim of replacing “the government of persons by the administration of things”. Žižek says that “the future of Europe is an open question: the disorientation of the crisis offers an opportunity for revival”. He has endorsed Yanis Varoufakis’ DiEM25, aimed at forging an alternative ‘social Europe’, and says “the most precious part of Europe – our contribution to civilization – is the social protections”. Like Varoufakis, he argues that continental solidarity is the only way to deal with cross-border challenges, from the environment to the refugee crisis. Žižek admires how the EU has “imposed standards on anti-racism and women’s rights” across the board, but laments its handling of the Eurozone crisis. He suggests the problem with the EU is not its lack of accountability, but its lack of ability. If only the elite were competent, they could administer to our needs!

Žižek’s growing scepticism of democracy reflects his frustration with radical politics. “It’s a very strange situation: this crisis should be ideal for the Left, but it doesn’t have any answers”. He is tired of the mass rallies without a plan, whether in Syntagma or Tahrir. “I am fed up of these demonstrations of one million people – they are bullshit. A short period of enthusiasm, where we are all together crying and bonding – and then? Ordinary people see no change”. Žižek feels that the Left’s tepid varieties of social democracy are impotent in the current climate, having failed to address the challenges of globalization. This is no more evident than in Greece: “Syriza exemplified this true tragedy: one day they win, and the next day they surrender. It is not a ‘betrayal’, but a genuine tragedy – a radical dead end”.

It’s tempting to speculate that Žižek has not only broken with democracy, but with the Left itself. After all, the state provision of goods and services is not exclusively a Leftist project – many patrician pre-democratic cultures performed it, often with a degree of consent. “Less and less I trust the Left”, he says; “what was said of Yasser Arafat is true of the Left – it never misses an opportunity to miss an opportunity”.

There are various contradictions here: Žižek acknowledges that traditional statist models are redundant, but waxes lyrical about “bureaucratic socialism”; he desires “an authentic revolution”, but isn’t so keen on taking to the streets; he laments “Asian values capitalism” (more truthfully termed ‘authoritarian capitalism’), but downplays democratic mandates; he decries “totally impenetrable institutions” but says “I want efficiency, not transparency”; and so on and so on. But even with these paradoxes (as he would term them), he offers illumination about the challenges ahead.

What struck me most about our conversation is not Žižek’s disillusionment with the Left or his aversion to democracy. Instead, it is what he calls his “secret dream”, of a settlement that transcends political activity. I sense his “emancipatory vision” is no longer about liberation from oppression, but about liberation from politics itself. If Europe does have a “unique contribution”, as Žižek terms it, maybe it is this “sense of an ending” described by Hegel (his favourite philosopher); of the longed-for deliverance from the weight of history, to a realm beyond the burden of ideology.

About the authors

Slavoj Zizek is a psychoanalytic philosopher and cultural critic. He has published extensively on Hegel and Lacan, and is the author of Against the Double Blackmail (Allen Lane, 2016)

Benjamin Ramm is editor-at-large at openDemocracy. He writes and presents documentaries for BBC Radio 4 and the BBC World Service. Follow him on Twitter: @BenjaminRamm

Source: opendemocracy