BY: Ammar Maleki and Pooyan Tamimi Arab

he shooting of a passenger airplane in Iran on January 8th and the initial denial of firing rockets, shattered the Iranian regime’s credibility. When the evidence quickly piled up, exacerbating international pressure, the call for the truth swelled up across all of Iran.

Two television news presenters working for the state broadcaster IRIB resigned. A third apologized: “forgive me for the 13 years I told you lies.” Never in the past forty years was the regime forced and humiliated to acknowledge its crimes so publicly in this way.

The people’s aversion to lying and deceit in politics remind of the Iranian philosopher Ramin Jahanbegloo. In 2006, he spent four months in solitary confinement in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison. A state-run television program aired his forced confession to having operated to the benefit of Iran’s enemies. He has ever since defended the “Right to Truth,” inspired by Gandhi, in exile, as the proper response to political persecution and the entrenched culture of lies in the Iranian political system.

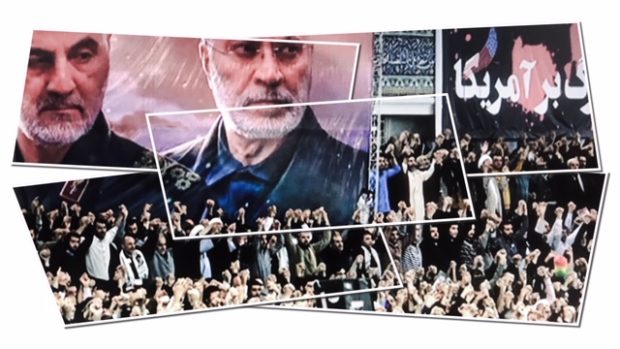

The funeral ceremony for general Qassem Soleimani, who was assassinated by an American drone attack, is a case in point. The world witnessed a huge crowd gathering in Tehran on January 6th, to honor the leader of the Revolutionary Guard’s foreign activities as a national hero. But three days later, when the facts surrounding flight PS752 became known, furious citizens took to the streets. They chanted in opposition to Soleimani and ripped posters with his picture from the walls. They reverted the image of Soleimani as a hero in the fight against ISIS, and shouted: “Revolutionary Guard, you are our ISIS!”

These citizens risked their lives after hundreds if not over a thousand were killed in November last year in street protests. For several days, the deeply felt need to express their disgust exceeded the fear of violence. Protestors turned against the theocratic system, against the Revolutionary Guard, and against the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. This was a rebellion in a state of becoming.

How is it possible that human masses mourn Soleimani’s death, so shortly after last year’s countrywide protests? And how can we explain the intense protests against him and his guard, so soon after his “martyr’s death”?

From a distance, one may be impressed to think of Iran as a polarized nation, comparable to the United States’ divide between Republicans and Democrats. In the context of closed, authoritarian states, however, the systemic state repression should be considered if one wants to find out more about ordinary people’s political attitudes. Even then, measuring Iranians’ political opinions is no sinecure. Conventional opinion polls by telephone or on the ground interviews would sketch a distorted image. Other evidence such as electoral turnouts and public rallies cannot be taken at face value, due to the regime’s Kafkaesque propaganda and punishment machine.

We nevertheless attempted to estimate the immeasurable opinion of Iranians through a large scale, anonymous, digital poll between March and April 2019, using the polling platform SurveyMonkey. The survey was spread via social media, accessible to roughly two-thirds of Iranians. Of the 204.000 respondents, 173.000 were aged 19 years and older and living in Iran. After weighting their reported political persuasions, gender, age, education level, and regional distribution, we were able to extract an effective sample size of approximately 20.000, which is very reliable. [The findings and an explanation of methods used can be read here].

The survey, published by GAMAAN, reveals that around 80% of the Iranian people would vote NO in a free referendum on the Islamic Republic as such. This unprecedented poll confirms years of qualitative research in the social sciences and the humanities regarding Iranians’ demand for democracy.

The simple answer to the paradox – that Iranians for and against Soleimani, as well as for and against the regime take to the streets – is that Iranian society is divided but not polarized. The ratio between the regime’s sympathizers and opponents is, according to our data, respectively 2 to 8. Shortly after our results were published in Persian, the platform Survey Monkey was blocked in Iran. Clearly, the regime seeks to hide ordinary citizens’ opinions and attitudes – whatever they may be.

Regime sympathizers, however, have been able to rally freely in public for decades and are awarded for doing so. This stands in sharp contrast to the threats against opponents on national television. It was made clear this January that whoever dare to demonstrate, will be themselves responsible for the ensuing bloodshed. Nevertheless, determined people still proclaimed in concert: “Islamic Republic, we don’t want, we don’t want.”

Lethal violence explains why a purported million people – 10% of Tehran’s population – can be seen mourning in high resolution in western television news coverage; in a country where filming is unsafe and where the state can totally shut down the Internet before opening fire on protestors.

In the meantime, academics and political commentators attempt to analyze Iran rationally through the lens of differences, between ethnicities, religions, ideologies, and classes, thereby often literally failing to capture the state violence, dishonesty, and lies. But perpetrators do know they are lying, such as the remorseful television presenter.

International pressure and access to evidence, as the case of the downed passenger airplane shows, can force the regime to uphold the right to truth. In our age, this inalienable right knows no clearly defined borders. By combining relentless international scrutiny with laws and policies aimed to protect Internet freedom, Iranians can be supported in their struggle to replace the confederacy of deceivers with a democratic system that represents and accommodates the will of all.

Ammar Maleki is assistant professor of political science at Tilburg University.

Pooyan Tamimi Arab is assistant professor of religious studies at Utrecht University.

source: opendemocracy

The article is an updated and edited version of an opinion piece published in Dutch by NRC Handelsblad