A pioneering new history on the cultural crossover between Persia and the West builds upon the tradition of Edward Said.

By: Steve Donoghue

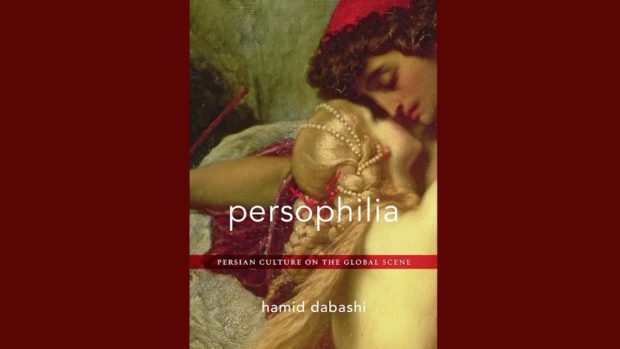

The first discussion in Hamid Dabashi’s Persophilia: Persian Culture on the Global Scene takes place on familiar ground: the enormous impact Persian literature and culture has had on the West for centuries.

Even restricting himself to what he refers to as the period of the East India Company, from roughly 1600 to 1872 (a period featuring “colonially instigated Orientalism”), Dabashi can only sketch an outline of the full extent of that influence and the masterworks of art and literature it inspired. He mentions the paintings of Leon Cogniet, Jean-Leon Gerome, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingre, Eugene Delacroix and others, the sumptuous music of Mozart (1782’s The Abduction from the Seraglio), Leo Delibes (1883’s Lakme, set in India), Puccini (his 1926 Turandot, set in China), and of course Handel (specifically his 1738 Serse, set in Persia). The writings of such disparate authors as Nietzsche, Goethe, Byron and Ralph Waldo Emerson are also cited.

Perhaps most emphatically of all is Montesquieu, whose 1721 book Persian Letters prompts a typically multi-pronged question from Dabashi, who wonders, “why would arguably the most prominent political theorist of the Enlightenment period, the very father of European and subsequently American constitutionalism, write a book like Persian Letters?”

The answer to such questions is caught up in Dabashi’s description of a great shift that occurred as Persian court culture migrated to the West, where its writers and poets found themselves excluded from the corresponding western courts and thus thrown into what Dabashi calls “non-courtly space (the emerging public sphere), which they called Vatan/Homeland.”

These displaced courtly artisans faced an uphill struggle to thrive among the European powers that were colonising and in some cases conquering parts of the Islamic world: “Persian literature had to learn to breathe in different languages, cultures, and climes. Persian literature was thus subjected to a set of multiple shocks – being out of its own royal courts, not being admitted to new courts, being forced into a public sphere entirely unknown to itself, and also finding itself rendered into alien and even inhospitable languages.”

Looming over any such discussion of the problematic dissemination of Persian culture into the world of European imperialism are two key texts which Dabashi acknowledges early on in his own book: Raymond Schwab’s 1950 The Oriental Renaissance and of course Edward Said’s 1978 Orientalism. And yet, as formative as these books are, there is an element of courteous impatience with them running throughout Persophilia, impatience especially with the often one-way nature of their discussions of East-West cultural interactions.

In part, it is this impatience that drives the second major discussion taking place in Dabashi’s book, which characterises those East-West cultural interactions as a cycle rather than a one-way street.

After all, as our author points out, “the founding fathers of contemporary Persian prose and poetry” – figures such as Mohammad Ali Jamalzadeh, Nima Yushij, Bozorg Alavi, Seyyed Hassan Taqizadeh, and Mojtaba Minovi – were all European-educated and often deeply influenced by European culture. Such figures and their readers, both abroad and especially back home, facilitated an exchange that Dabashi contends is too often overlooked by contemporary studies: once impressions of how Persian culture was being perceived and adapted in the West trickled back to the courts of Iran and its other countries of origin, in what ways were the cultures of those countries affected? In what ways did this bring about what Dabashi describes as “subsequent generations of Iranian public intellectuals reimagining themselves and their homeland in the larger, global public sphere”?

As Dabashi notes, Persian culture’s literature entered “the European bourgeois public sphere” even before the bulk of its merchants, students or travellers did in person: writers such as Goethe, Edward FitzGerald (with his immensely popular English-language version of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam), Matthew Arnold or Montesquieu all seeded the European intellectual ground, which in turn helped give rise to a whole variety of social and intellectual movements in Europe and beyond, from the Enlightenment to romanticism to transcendentalism.

Dabashi’s descriptions of this “thriving, vicarious life” lead by Persian language and literature occupy several chapters of his book, with lively, contentious discussions of the literary atmosphere in which, as he puts it, “Sainte-Beuve praised Ferdowsi, Goethe and Nietzsche admired Hafez, and Joseph-Ernest Renan celebrated Sa’di.” Persian-influenced works such as Goethe’s Westostlicher Divan, Thomas Moore’s Lalla-Rookh and Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum “soon became staples of literary learning for the bourgeoise public at large.”

Dabashi spends a very satisfying amount of time with such key figures as Arnold, whose 1853 poem Sohrab and Rustum is based on one of the most famous episodes in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, and Nietzsche, whose Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-1885) was so transformative to its author and to future interpreters. “Through romanticism and against romanticism, Nietzsche was finding his way to a superior light,” Dabashi writes. “Hafez and Zarathustra were waiting for him.”

Along the way, Dabashi proves himself once again a master of many rhetorical registers – something that will come as no surprise to readers of his sharp-tongued book Can Non-Europeans Think? In the same chapter, he can go from a sensitive and light-fingered reading of the West’s embrace of the verses of Rumi to a fast-paced assessment of Heidegger in which every sentence covers a lot of ground and makes all the right enemies: “The misplaced criticism of Heidegger’s critique of modernity and Enlightenment-based humanism, which invariably collapses into the perfectly legitimate one of his Nazi affiliation, has made the liberal humanists strange bedfellows of such ideologues of capitalist modernity as William Bennett, Allan Bloom, and Dinesh D’Souza.” Dabashi is himself first and foremost a careful reader, a reader of contexts, and in Persophilia it’s always less careful readers (and their works) who are most consistently outpaced.

It’s this careful reading that singles Persophilia out as a work of quietly revolutionary insight. By following the work of Persian art and literature not only out of its original courtly environment and into conflict and often collusion with the West, Dabashi adds a much-needed undercurrent to the entire school of thought that originated with Said’s Orientalism.

By following that same Persian art and literature, now itself transformed by its time in the public space of the West, back to its nationalising and sometimes revolutionary homelands, he completes the picture of a grand, prolonged, and almost entirely unplanned cultural cycle. In his version of that cycle, the “romancing” of Persia is just one facet of the whole process, although in his hands it is a fascinating facet, ranging from Benjamin Franklin “trying to pass off a story from Sa’di’s Golestan as a lost passage from the Bible … to the homoerotic narrative built around the character of Bagoas as Alexander the Great’s lover in Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy … to the Cyrus Spitama character in Gore Vidal’s Creation.”

That “wide and wondrous gyre”, in Dabashi’s telling of it, eventually widens to suck down the very idea of colonial isolationism and exceptionalism (as he pithily puts it, “the devil of Orientalism is in the details of Persophilia”). When Persian culture begins a process of “circumambulating the globe”, it set in motion a series of artistic adaptations it could neither foresee nor control, and this was by no means a bad thing. By so convincingly describing a grand cycle rather than any series of discreet inoculations, Dabashi actually paints a more optimistic portrait of cultural exchange than was dreamt of by thinkers like Goethe or Arnold, one in which the sharing of artistic heritages, while shocking, can also be “invigorating, provocative, [and] self-regenerative”. Persophilia deserves to become a standard benchmark in the study of that unsettling regeneration.

This book is available on Amazon.

Steve Donoghue is managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.

from: thenational.ae