A legacy of overseas expansion

Very few of my elderly relatives dared say during their lifetime where they wanted to be buried – they feared that to talk about it was to tempt fate. No salesman ever managed to get them to buy funeral insurance. They stashed their life savings in secret hiding places, reasoning that one day the money would come in handy. Even when his life was drawing to a close, my grand-uncle Kon Sjak didn’t utter the wish to be buried in a Chinese cemetery. When he had finally been laid to rest in Oud Eik en Duinen cemetery in The Hague, his children could rightly say that he had been a model immigrant. He spoke Sranan, English, Dutch and three Chinese dialects, including Hakka, his native tongue. Wherever he lived, he had adapted. The fact that he lay among the Dutch rather than the Chinese in the realm of the dead was the ultimate proof of successful integration.

It was different in the case of my grandmother. Regarding life’s major events, she’d had little to choose. Everything would be more or less determined by others: from the cradle, when it was arranged who she would marry, to the grave. At her funeral we performed all the rituals: we burnt joss sticks and Hell banknotes, and placed dried food – along with the mandarins she was so fond of –on her grave.

The next day my brother Akko happened to drive past the Chinese cemetery. He spotted her grave right away – it lay in a section close to the road – as the sunlight fell right on it, lighting up the pink marble. The orange mandarins stood out brightly against the stone, and a small bird was pecking around on the grave. As Akko cautiously slowed to a crawl, the bird suddenly took flight. She flew parallel with the car, then veered round and rapped the windscreen twice with her beak, as if in greeting. As to what kind of bird it was, Akko didn’t have a clue. My brother is very down to earth and much too preoccupied with everyday concerns rather than fauna and flora or spiritual notions. The subject of the bird came up during our annual maintenance of her grave; he said it was the only bird that had ever greeted him. Akko was the apple of my granny’s eye, her only grandson. His existence made her feel that her life had not been in vain.

Our ancestors gave us life, their descendants commemorate them eternally. Their tombs are cleaned, their souls brought to rest. The Chinese rituals of today are no different to those of a century ago. The care of graves did not escape the notice of missionaries in nineteenth-century China. In their eyes it was a heathen tradition, not a religious practice. As a result, mission churches actively sought to combat such paganism as late as 1915.

The missionaries mingled with Chinese folk thus gaining a foothold on Cantonese soil and its communities. Among them was an evangelical couple by the name of Wilhelm and Elizabeth Oehler, who were sent to China by the Evangelische Missionsgesellschaft Basel, a Swiss missionary society. They settled in the district of Bao On, where they attracted loyal disciples from the Hakka village of Chonghangkang.

(-)

In godforsaken places

The first time I heard the name Oehler mentioned was at a Sunday lunch in the Grand Garden Restaurant in Rotterdam. The baby daughter of my cousin Kelly had been christened that morning in the church of the Evangelische Broedergemeente (Evangelical Brethren) on the stately Avenue Concordia.

I asked Kelly’s father-in-law Robert how he came to be such a faithful member of that church. I’d thought that the Surinamese Chinese community mostly claimed to be Catholic. He told me that Protestantism had come to his grandfather’s village over two generations ago, in great part due to the efforts of the Oehlers. I asked Robert whether he could tell me more about this later in a quiet setting, and so he invited me to visit him at his home.

Among the papers left by his grandparents were a few faded photos dating from the 1980s, showing Chinese graves. Only one headstone in Chonghangkang, his ancestral village, featured a cross, and that was the one marking the grave of his great-grandfather. Leafing through translated missionary booklets in the Dutch-language I came across a bundle of photocopied letters, written in German. The sender’s name was Elizabeth Oehler.

*****

Around 1900, in the province of Guangdong, Elizabeth travelled through villages in which there were no longer any young men. They’d gone abroad, leaving their wives and children behind, in hopes of making their fortune. Often their wives waited in vain for their return, sometimes for up to twenty years, by which time it was the eldest child’s turn to be the family breadwinner.

Robert’s grandfather Chin On had chosen a different path: he was keen to become an evangelist. Called A-On for short, he was the eldest son of Ming That, head teacher in Chonghangkang. When A-On came of age, the Oehlers trained him as a pastor. His wife Loi Giao was also given the opportunity to spread God’s word in Hakka, their mother tongue. Elizabeth had long noticed that she was different to the other peasant women in the district. Loi Giao always looked elegant, in a carefully selected outfit. She had finely arched eyebrows and her hair, brushed flat with camellia oil, was encircled by a velvet band. She was the most hard-working of all women that Elizabeth had encountered in the entire district.

In A-On, Elizabeth saw a boy not yet fully grown, whose almond-shaped eyes seemed to her to betray vanity and a sly nature. His pay being so meagre, however, she did not foresee him becoming an obstacle to the evangelists. As the missionaries brought the Western world to the poor, especially the Hakka, they sowed apprehension among the Chinese. They were the vanguard of Western imperialism, it was feared, raising the spectre of religious, political and economic expansion. The Oehlers persevered, however, and their system of training the local Chinese people to spread the Gospel was widely adopted by subsequent generations of missionaries.

(-)

In 1910, after a period working as a missionary, A-On decided to leave China for Surinam, where he hoped to be able to earn enough to pay off his father’s debts. Loi Giao, by then pregnant, was determined not to remain behind as a single mother, and left for Surinam a few years later with their son.

Back in Europe, Elizabeth Oehler stayed in touch with the Evangelical Brethren, who after 1948 expanded their missionary work to the Chinese community in Surinam (Ed.).

(-)

When there’s a fire, flames will be smothered

A different fate awaited the men who left their Hakka villages in the hope of making their fortunes. The families they left behind knew nothing of what had happened to their menfolk far away, on the northern shores of South America. When the first migrants arrived on the continent on the other side of the ocean, there was great concern back home. All that would later remain of the men who had left, were registration papers, showing nothing more than their names and places of birth. For the rest they were persons unknown, all trace of them erased. By intuition the men knew that their departure would have huge consequences. Because leaving would make it impossible to tend the graves of their ancestors, to scare away the evil spirits with the din of fire-crackers. Its importance was spelt out in the ancestral temples of Hakka villages, calligraphed in elegant script, from right to left on three columns:

The benevolent power of our forefathers will never wane.

It makes us prosper, and causes some to live to a great age and have many sons.

Their intentions towards their descendants bring good fortune: ever greater wealth, ever greater standing, ever greater well-being and peace of mind.

That they would be treated brutally on the voyage was something the peasants couldn’t have known. And even had they been able to read a small article that later appeared in a Singaporean newspaper, about a Dutch ship that had set sail with 1,100 passengers on board – twice as many as it had been built to carry – they might well have shrugged. So what if during the eleven-day voyage the passengers were only given eight meals? They were going hungry anyway, did it matter whether it was on land or sea?

And so what if 100 passengers had died during the crossing? Numbed as they were by the deaths of so many of their family in their home village, mere figures in a newspaper would have meant little to them. Nor would they have been much affected to read that five of the thousand surviving passengers were trampled to death in the stampede for drinking water when they finally disembarked. After all, the terrible pangs of thirst could not be expressed in statistics. So it’s doubtful whether the accounts of these horrors – summarized only in numbers – would have deterred them.

If the crowd of passengers hadn’t complained to the shipping company after this harrowing voyage, the incident would never have been reported in the press. Their grievances would have been dealt with, purely as a matter of business. The shipping company was not concerned by the charge that it had caused the deaths of a hundred passengers, or by complaints about lack of food and water during the eleven-day voyage. The thing that really stung was having to refund those hundred tickets to the surviving relatives.

In his book Wij slaven van Suriname (We Slaves of Surinam), Anton de Kom describes how in 1858, at the urging of planters, the Dutch consul in Macau recruited 500 Chinese labourers, known as coolies. When it emerged that no one wanted to hire them as long as slaves could work for free, the governor altered the contract that had been drawn up between the planters and the labourers without informing the latter. The planters treated them like slaves, and when they rebelled, had them beaten with a bamboo cane.

After the abolition of slavery in 1863, men continued to be recruited on the island of Macau in defiance of the law, so that labour on the colonies could continue. It was common knowledge that during the four-month voyage, at least half the ‘passengers’ died as a result of scurvy.

Sooner or later, many peasants became aware of the increasingly grim conditions aboard the coolie transports. Bloody mutinies regularly broke out on ships bound for the Western colonies in the Caribbean. Any Chinese peasant travelling on such a vessel between 1865 and 1871 could well have found himself caught up in such a mutiny.

There was no shortage of witnesses, therefore, to the criminal nature of the transports. But the simple Chinese peasants fortunate enough to survive such a voyage were extremely reluctant to speak. Investigations of disasters at sea began with the testimony of the European crew, starting with the captain. Take the case of a ship that sank in 1871, whose captain declared: ‘The vessel lay in Macau harbour, awaiting the delivery of contracted labourers. Chinese intermediaries had recruited passengers for the ship.’ When asked if they were registered, or if contracts had been drawn up, the captain was at a loss to answer. He was in charge of transport, not the men being transported. He continued his account: ‘Under supervision of Europeans, the Chinese who had been recruited were led to a warehouse in Macau. There they were well treated and well fed.’ What the captain neglected to say was that the Chinese had walked into a trap. The migrants initially had high expectations, as they were indeed fed. But they were then forbidden to go outside, the Chinese told the interrogators. Armed men stood guard and threatened them with six years in jail for desertion if they left the warehouse.

It contrasted starkly with what had gone before: a recruiting agent had lured them with the promise of eight dollars a man on arrival at their destination. They would be given new clothes, a free passage to Vietnam and their employer would pay them four dollars a month. Vietnam sounded attractive; close to their homeland of China.

On 4 May 1871, when 650 passengers had been gathered, they were marched in columns to the ship, where an armed crew awaited them. More guards stood on the quayside. All these precautionary measures had been taken because the labourers were in fact not bound for Vietnam at all, but for Peru. Had they been aware of what lay in store for them, they would never have gone to the warehouse in Macau. The Chinese middlemen knew that all too well.

The inhuman conditions that migrant labourers often met with led many to take their own lives. Suicide was in fact the most common cause of death among the Chinese in Peru. This piece of news was spread by Chinese students who’d crossed over to America and seen The New York Tribune’s coverage of the coolie trade in Latin America. So the Chinese knew, at last, why no peasant who’d supposedly left for Vietnam ever returned to his native village.

Once aboard the ship, the 650 passengers were given only scanty supplies of food and water. Locked in the hold they were deprived of light, apart from stray rays of sunshine or moonbeams falling through cracks in the timbers. As time went on, they must have realised that they certainly weren’t bound for Vietnam.

After two days at sea, twelve of the recruited labourers were put to work cleaning the deck, herded back to the hold like cattle. One of the men seized the opportunity to snatch a box of matches that had been lying on deck. As they approached the hold they knew they had little to lose: it was a choice between a quick death at sea or a slow one from forced labour at some unknown destination. When the crew member leading the way opened the hatch, the twelve men put up a fight, but they didn’t stand a chance against so many armed sailors. They were overpowered and driven down into the hold, then the hatch was slammed shut.

Panic broke out below deck. Now everyone knew that they had been trapped into slavery. If they did not take fate into their own hands, they would never return. They hit on a desperate solution: they would use the purloined matches to light a fire. When there’s a fire, flames will be smothered, they reasoned. The crew would surely want to save the ship, perhaps even be moved by compassion towards the Chinese.

The captain must have known from experience how to deal with emergencies during forced labour transports: he kept the hatch tightly shut. At the inquiry he claimed that he and his crew had tried to extinguish the blaze – alas in vain, he said.

When one of the sailors opened the hatch and the panic-stricken Chinese tugged at his clothes, the captain ordered the entire crew to get into the lifeboats and row away from the burning ship, leaving the passengers to their fate. As the last boat pushed off, one of the sailors broke the lock on the hatch and called down to the Chinese: ‘Fly away!’, before leaping into the boat.

About fifty of the Chinese men closest to the hatch managed to claw their way up to the deck. As the flames raged through the ship, they were able to jump into the sea just in time, and cling to pieces of wreckage. For 600 men and boys, though, it was too late. The ashes of the vessel and those aboard her sank beneath the waves and dissolved in the ocean. That happened on 6 July 1871.

When more mutinies broke out on ships in the years that followed, suspicion grew concerning the witness testimony of their European crews. Local officials had to be condoning this human trafficking and keeping the Chinese passengers in the dark about their real destination.

The authorities were pressurised to prohibit coolie transports to Peru and Cuba. Meanwhile, though, another 5,000 Chinese had been recruited and taken to warehouses in Macau where they waited to board ships.

The Chinese government subsequently decided to ban all non-state-controlled recruitment of labourers and to impose the death penalty for human trafficking, so as to protect its citizens from the Wild West practices of European colonial entrepreneurs. Only free migrants were allowed to take ship to the colonies, and they had to do so at their own cost, or be funded by relatives. It was expressly forbidden for the captains of migrant ships or the owners of overseas plantations to fund such passages up front – them being the ones who benefited so royally from Chinese emigration.

The extracts above are from the essay ‘In van God verlaten oorden’

ISBN-nummer 978-90-830392-0-6

It can be ordered via [email protected]

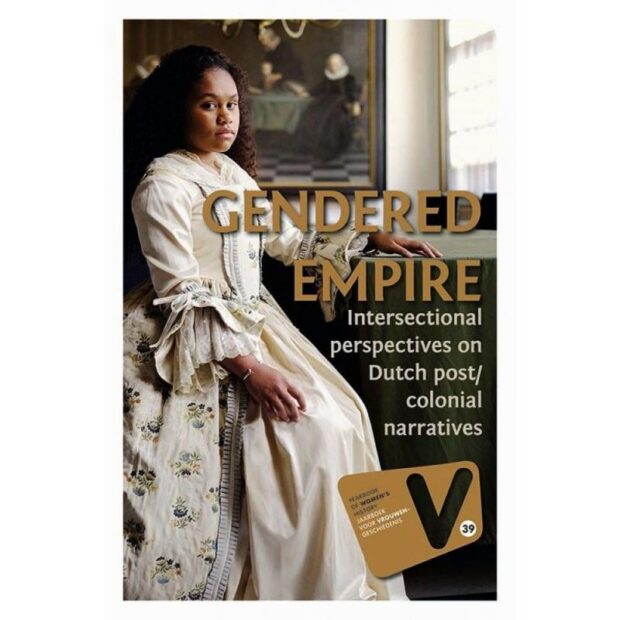

And is one of the contributions in ‘Gendered Empire – intersectionale perspective on Dutch post-colonial narratives’

to be ordered here under